Support for this article was provided by the Pulitzer Center.

Last month, a parade of vehicles wound its way through three cities in Brazil, releasing clouds of mosquitoes into the air. The insects all carry a secret weapon — a bacterium called Wolbachia that lowers the odds that the mosquitoes can transmit the dreaded dengue virus to humans.

This is the world’s largest ‘mosquito factory’: its goal is to stop dengue

These infected mosquitoes are the latest weapon in Brazil’s fight against dengue, which infects millions of people in the country each year and can be fatal. A biofactory that opened in the town of Curitiba in July can produce 100 million mosquito eggs per week — making it the largest such facility in the world. The company that runs it, Wolbito do Brasil, aims to protect about 14 million Brazilians per year through its Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes.

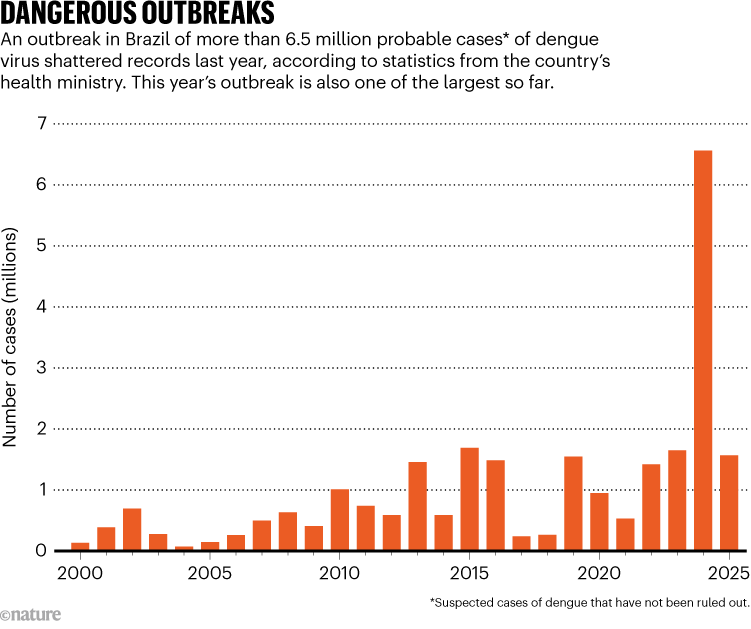

That will come as welcome news for the Brazilian health officials battling the rapidly growing threat of dengue. In 2024, the country experienced its worst outbreak yet: with 6.6 million probable cases and more than 6,300 related deaths. This year’s outbreak, although less severe, is also one of the highest on record, with 1.6 million probable cases so far (see ‘Dangerous outbreaks’). And the problem is spreading. Argentina, Colombia and Peru also experienced record-breaking outbreaks in 2024 and have seen a sustained increase in cases in recent years. Across Latin America and the Caribbean, deaths from dengue last year totalled more than 8,400 and the global figure reached more than 12,000 — the highest ever recorded for this disease.

SOURCE: Brazilian Ministry of Health

As outbreaks grow larger and the crisis becomes more urgent, the Wolbachia method isn’t Brazil’s only bet. A locally produced dengue vaccine is now awaiting approval by the country’s drug-regulatory agency, and its health ministry expects to start administering tens of millions of doses by next year.

These twin advances offer some hope to other countries — in the region and beyond. Driven by forces such as climate change, mosquito adaptation, globalized trade and movements of people, dengue is becoming a crisis worldwide, with an estimated 3.9 billion people at risk of infection. As Brazil rolls out its armies of infected mosquitoes and a vaccine in the coming year, the rest of the world will be watching closely.

The local approach

Currently, there is one main dengue vaccine in use around the world: Qdenga, licensed by the Japanese pharmaceutical company Takeda. The vaccine has been approved in many countries, including Brazil, which was the first nation to include it in its public-health system.

However, Qdenga’s roll-out in Brazil is limited. The country bought nine million doses of the two-dose vaccine this year: enough to vaccinate 4.5 million of its population of more than 210 million. So far, Qdenga has been administered to children between the ages of 10 and 14, one of the groups most likely to end up in hospital after contracting dengue, together with older people. Its safety and efficacy have not yet been tested in adults aged over 60.

The main reasons for such a limited roll-out in Brazil are availability and cost. Even though Brazil secured Qdenga from Takeda at one of the cheapest prices in the world —around US$19 per dose — the cost is still high compared with other vaccines. And even in the most optimistic scenario, the maximum number of doses Takeda could provide by 2028 is 50 million — enough to vaccinate 25 million people. What’s more, for people who have not had dengue before, clinical trials did not show Qdenga to be effective against all four variants — or serotypes — of the dengue virus.

When will dengue strike? Outbreaks sync with heat and rain

Brazil is trying to address all of those limitations with its one-dose vaccine candidate, developed at the Butantan Institute, a public biomedical research centre in São Paulo. “Having local production capacity gives us independence on decisions — how many doses we need, and at what speed to vaccinate,” says Esper Kallás, Butantan’s director. “You can practise prices that are more suitable and absorbable by a public-health system such as Brazil’s.”

Butantan is also optimistic that its vaccine will be effective against all four forms of dengue. Severe disease usually occurs when a person is infected by a different serotype to their first infection. That means that a successful vaccine needs to generate antibodies for all four serotypes without triggering severe reactions, which makes it a difficult vaccine to develop. “It was indeed a challenge, as each serotype behaves differently,” says Neuza Frazatti Gallina, manager of the viral vaccine development laboratory at Butantan.

The vaccine’s development began at the US National Institutes of Health in the late 1990s, where scientists transformed dengue viruses they had isolated from patients into weakened vaccine strains that could trigger the production of protective antibodies without causing disease. In 2009, Butantan extended that research by working to solve the challenges of combining the four strains into a vaccine.

Eggs of mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia bacteria. After hatching, the mosquitoes will be released to prevent the spread of dengue.Credit: Xinhua/Shutterstock

After testing 30 formulations, Butantan arrived at one that proved highly effective in preventing infections, according to the preliminary results of a phase III trial involving more than 16,000 volunteers in Brazil. The study reported that two years after vaccinations, the formulation was 89% effective in preventing infections in people who had previously been infected with dengue, and 74% effective in those with no previous exposure1.

“It was a well-designed trial,” says Annelies Wilder-Smith, who is team lead for vaccine development at the World Health Organization (WHO). But she says one limitation of the trial is that it was conducted in a single country, and therefore runs a risk that all four serotypes were not circulating at the time.

In fact, serotypes 3 and 4 were not prevalent during the data-collection period of the clinical trial, although they are now circulating in Brazil. Butantan researchers suggest that the vaccine will be effective against serotypes 3 and 4, pointing to data from a phase II trial2 in 300 adults that showed participants produced neutralizing antibodies to each of the serotypes. That study evaluated safety and immunological response in the short term, rather than looking at the vaccine’s long-term efficacy in preventing infections. The full results of the Brazilian phase III trial — which will provide data on long-term effectiveness — are not yet public and are undergoing peer review.

The vaccine is already moving through the country’s regulatory process. And although there’s still no certainty about when Anvisa, Brazil’s regulatory agency, will approve the vaccine, the government is counting on it. In February, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva announced that, starting in 2026, the Ministry of Health would be buying 60 million doses annually.

To meet that demand, Butantan is now producing the vaccine at its São Paulo facility. On its lush campus, an entire building is dedicated to churning out doses.

Regarding the vaccine’s approval, “We are very confident,” says Kallás. “We also anticipate that there is a very prominent need to have this product in the arms of people. So we hit the road running and started producing vaccines late last year.”

Although Butantan’s production efforts will focus initially on meeting Brazil’s need for millions of doses, Kallás expects that the vaccine could reach other countries. Butantan has been discussing with its development partner — the pharmaceutical giant Merck — and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) how to make the vaccine accessible to other countries. The logical first step, he says, would be to roll it out through PAHO to Latin America and the Caribbean, and then to other regions.

In the meantime, Merck is developing a potential vaccine for Asia with an almost identical formulation, which builds on the knowledge that Butantan has developed. In a statement, the drug firm said that Butantan is “sharing clinical data and other learnings”. In June, Merck started enrolling participants for its own phase III trial. “All the data, experiences and insights they have collected with the Butantan vaccine will be helpful,” says Wilder-Smith.

Infecting mosquitoes

While Butantan awaits news about the vaccine’s approval, the Wolbachia method to control dengue is gaining momentum. The World Mosquito Program (WMP) — a non-profit group of companies owned by Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, where the strategy was developed — has operations in 14 countries, including Vietnam, Indonesia, Mexico and Colombia, but Brazil leads the way in terms of the scale of its expansion.

The method’s arrival in the Americas is tied to Brazilian researcher Luciano Moreira, now the chief executive of Wolbito do Brazil. Wolbachia is naturally present in around 50% of insects, but not in the mosquito species Aedes aegypti, which is the main transmitter of dengue and many other viruses.